I first noticed the silence on an unremarkable Friday in March 2023. Silicon Valley Bank—a regional lender most people outside the tech bubble had barely heard of—slipped into receivership with little more than a terse press release.

There were no hysterical queues, no frantic television tickers, only a faint ripple in the news cycle before attention pivoted elsewhere.

Yet the post-mortem revealed a story we have seen many times: managers had calibrated their models to the comfortable, low-rate decade after 2010, treating that brief stretch of history as if it were a law of nature. When rates finally snapped back to 1980s territory, the bank’s tidy spreadsheets could offer nothing but a shrug.

That quiet implosion nudged me back to Nassim Taleb’s turkey parable—the bird that enjoys a thousand generous breakfasts and therefore “knows” the world is benign until the day before Thanksgiving.

Taleb uses the story to illustrate what he calls the inverse problem of rare events: the most damaging outcomes live in the thin, poorly lit tail of the distribution, precisely where our data are scarcest. Instead of beginning with theory, Taleb asks us to start with ignorance—acknowledging that the tail is, by definition, a place we seldom visit. His “confirmation-box” diagram of The Fourth Quadrant makes the point graphically: once the data fit neatly inside the safe zone, we stop asking whether an uglier region exists just beyond our sample.

The eerie part is how often that blind spot recurs across domains that share nothing on the surface.

Info:

In May, my 3rd cohort course, "Guide to AI in Security Risk Management," starts.

If you want to learn how to leverage AI across the entire Security Risk Management process—including risk quantification—this course is for you.

In just a few hours, you'll go from 0 to building your own quantitative risk models.

No technical skills required.

Join now—spots are limited!

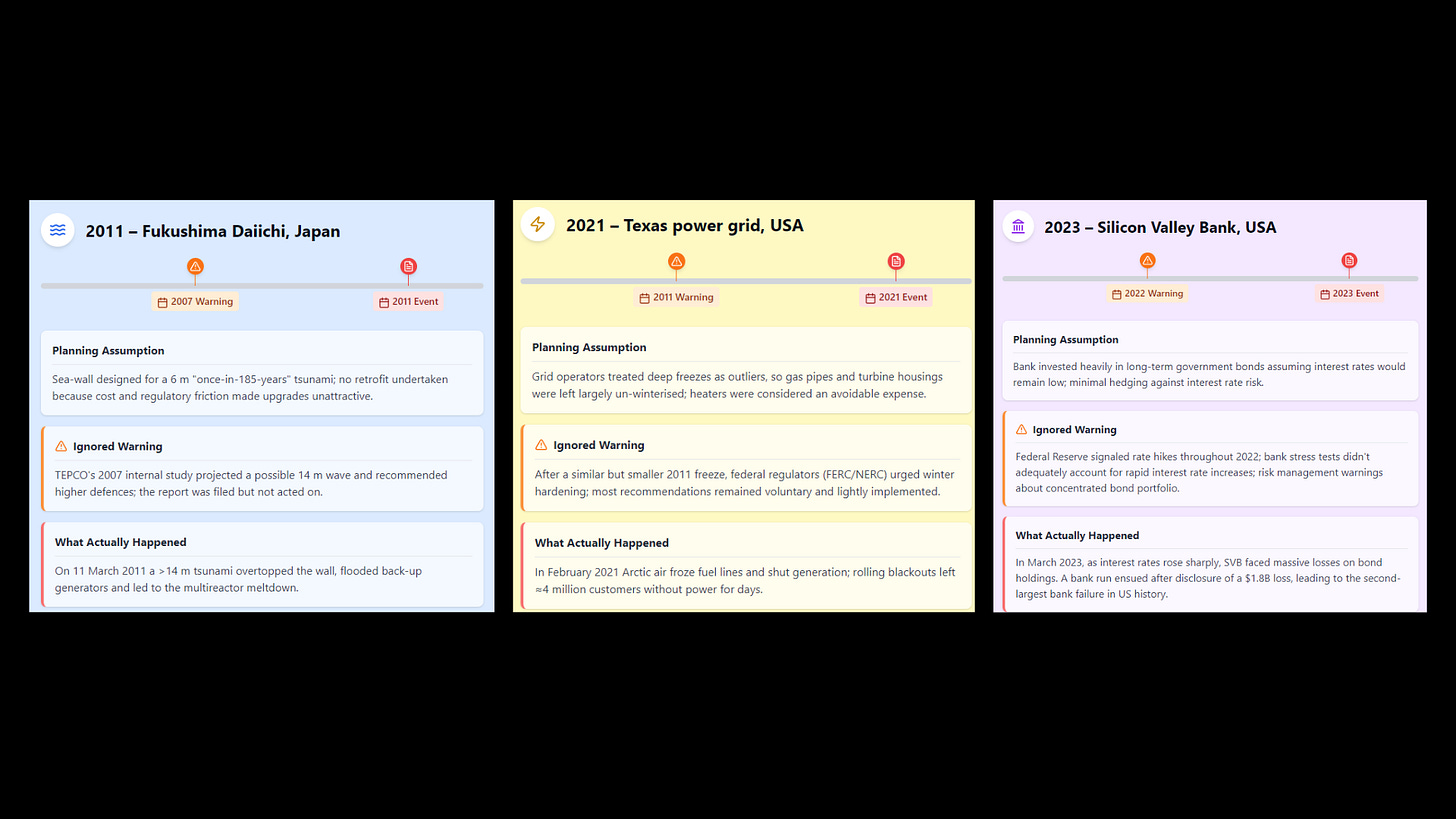

In 2011, engineers at Fukushima Daiichi built their sea-wall for a six-metre wave, labelled “once in 185 years.” A 2007 internal study flagged a possible fourteen-metre tsunami, but retrofitting looked expensive and politically awkward, so the paperwork stalled. When the larger wave finally arrived four years later, it sailed over the wall and straight into the back-up generators.

A decade later—and half a world away—Texas grid planners faced the mirror image of the same mistake. Years of mild winters convinced officials that heaters on gas pipes and turbine housings were an optional luxury. Then February 2021 delivered a sharp Arctic dip, freezing fuel lines and forcing rolling blackouts that left four million residents literally in the dark.

Add SVB to the list and you have three industries—banking, nuclear power, electric utilities—sharing one unifying trait: the comfort of recent experience was mistaken for a portrait of the possible.

Why doesn’t the obvious fix—“collect more data!”—solve the problem?

In thin-tailed settings like assembly-line defects or human heights, the law of large numbers tames uncertainty quickly; the fiftieth sample looks a lot like the thousandth.

In fat-tailed realms, Taleb shows that even ten thousand observations may leave the tail exponent swinging wildly (his simulation on page 12 is worth a look). The cruel twist is that the loss we care about compounds faster than our confidence grows. If we wait for the dataset to mature, we risk being retired—or bankrupt—before the statistics deliver clarity.

My own practice hasn’t abandoned models, it has reassigned them. I now begin by visualising the scenario I cannot afford—a bank run that drains deposits in hours, a wave that overtops the levee, a cold snap that stalls half the grid—and then I ask a brutally simple question: What is the cheapest buffer, hedge, or design tweak that survives that scene?

That mindset legitimises obvious but often under-budgeted line items: thicker capital cushions, spare pumps, dual-fuel turbines, winterised pipe jackets. It also elevates small bets with asymmetric payoffs—out-of-the-money options, modular pilot projects, flexible supply contracts—that cost little in calm times yet bloom when the improbable happens. The decision threshold is set by the worst believable outcome, not by the mean of the parameter estimates.

If you want to bring this conversation into the boardroom, try three deceptively simple questions:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to On the Edge of Resilience to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.